Why even in a good year, it's nearly impossible for the Moneyball Rapids to win a trophy

And why that's not really a bad thing, or that shocking.

On page 124 of Michael Lewis’ ‘Moneyball’, you will find the following :

Before the 2002 season Paul DePodesta had reduced the coming six months to a math problem. He judged how many wins it would take to make the play-offs: 95. He then calculated how many more runs the Oakland A’s would need to score than they allowed to win 95 games: 135. (The idea that there was a stable relationship between season run totals and season wins was another [Bill] James discovery.)

This is a core principle of the book, and therefore of the moneyball concept itself: winning in sports is simply solving a math problem. How do you construct a team that can produce more runs (or goals, or touchdowns) than the other team, within a certain margin of error? For soccer, the good people at American Soccer Analysis came up with this number back in 2019. The answer is: Estimated Season Points = 0.662 * (Goal Differential) + 46.6. Plug that into MLS’ 2024 results, you see that LAFC had a GD of 20 and produced 64 points. The formula above indicates LAFC were expected to produce 59.84 points. For the Colorado Rapids, they had a GD of +1; they were expected to produce 47.26 points, and, again, overperformed to produce 50 points.1

And then on page 275, Billy Beane, the Major League Baseball General Manager who aggressively piloted the whole moneyball experiment, famously says this:

"My shit doesn't work in the playoffs. My job is to get us to the playoffs. What happens after that is fucking luck."

This is essentially my understanding of what happened to the Colorado Rapids in 2024; Pádraig Smith and Fran Taylor shrewdly built this team to get to the playoffs, and after that, a mix of individual talent and dumb luck took the wheel. That’s both why Colorado was so good during the Leagues Cup run in which they dispatched Club León, then Toluca, and then Club América and why they could not get past the eventual MLS Cup winners, LA Galaxy, in the first round. Averaged out across 34 games, patterns emerge, tendencies are revealed, and statistical flukes are smoothed over.

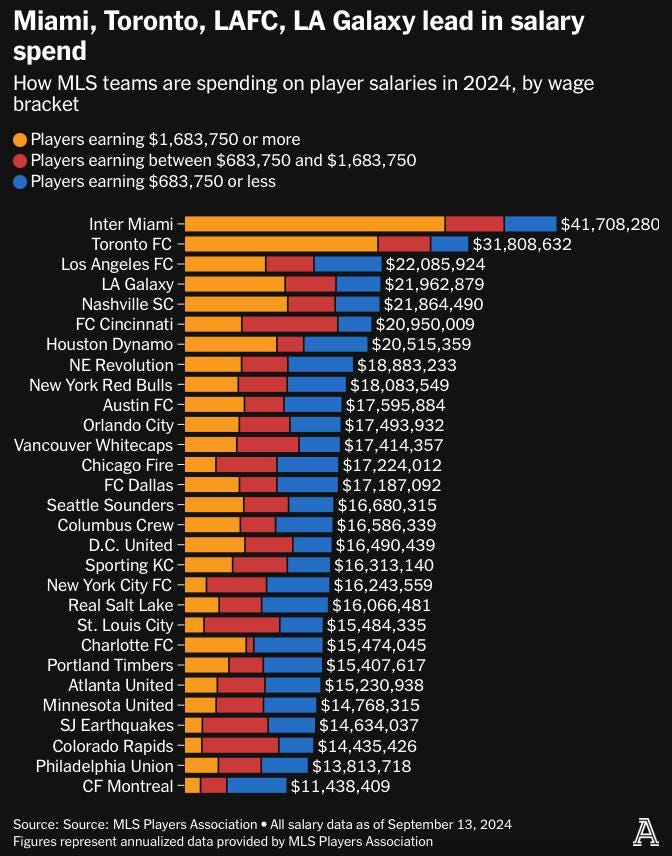

That doesn’t mean you can’t reliably construct championship teams: LA Galaxy and Inter Miami and LAFC have been doing that for several years. (I mean, also, duh, somebody’s gotta win the thing.) It’s just that there is a huge financial difference between ‘making the playoffs’ and ‘constructing a championship team.’ Take a look at MLS salaries in 2024:

Looking at this chart, you can both be impressed at the Rapids finishing 12th out of 29 teams on points AND feel a little hopeless about the ability for Colorado, spending $14.4 million, to compete with the two LA teams that spent almost 50% more than Colorado. Or Miami, who spent almost 3x what the Rapids did. This is what Billy Beane means when he says ‘My shit doesn’t work in the playoffs.’ You can reliably and cleverly construct a team that does not cost you a gazillion dollar that can be in the top half or top third of a given sports league. But it takes another order of magnitude of money to be amongst the elites.

The Moneyball approach to sports has (at least) two main principles: 1) everything can be reduced to data and numbers – so as long as you use the *right* numbers, you’ll be better than the next guy. At the time of writing, baseball was full of people who didn’t use numbers at all, or that used really dumb numbers like RBI (Runs Batted In). In fact, MLB used to give out the MVP award regularly to the player that had the most RBI in a season, and gave out the Cy Young Award to the pitcher with the most wins. Both of these ideas were bad. Regarding RBI, one player could hit 40 Home Runs with nobody on base and record 40 RBIs; another player could hit 40 Grand Slams with the bases loaded and drive in 160 runs. The MVP award would almost invariably go to the guy with 160 RBI, even though he had no effect on who was on base when he stepped to the plate.2 Wins was an even sillier stat. It was based on pitching with a lead for five innings or more: meaning it was around 50 percent dependent on how well the batters on a pitchers team did against the pitcher of the opposing team. That’s ridiculous. But for decades, major league front offices took it seriously.

Soccer hasn’t historically been great at descriptive analytical statistics. Go to most websites and they’ll display an outfielder players goals and assists. On defense, you might get tackles and clearances. But none of those is super worthwhile: A good striker on a bad team will hardly touch the ball enough to score a goal. A bad defender on a great team might see their teammates whip the ball around in possession so dominantly that they barely need to put in a tackle. So for years Colorado, among other smart teams across the globe have gone in search of the *right* numbers. I wrote about it waaay back in 2018. It’s a good piece. Go read it.

The Rapids today still use a bevy of proprietary metrics to analyze players and come up with numbers that mean something to Colorado. In the aggregate, on average, and over time, Colorado can get reasonably close to achieving predicted results. Plug in players in their prime at every position worth an above average Expected Goals and Goals Added, and you will finish above .500. Do that with players that somehow other managers have misused or players that have been undervalued, and you can moneyball your way into the playoffs.

But I’m fairly certain that what Billy Bean said almost 20 years ago still applies today. This shit doesn’t work in the playoffs. The sample size becomes ridiculously small. In one game or over four games, dominant players have outsized impact, and those dominant players often get paid non-moneyball type salaries.

Or you get what happened to the Rapids in Leagues Cup: luck creeps in. Better teams have an off day and the ball strikes the woodwork a bunch and they lose. All the smart teams know this, and that’s why, when faced with an overpowering opponent, the smart teams play defensively, concede possession, strike on the counter, and play for a draw and PK shootout. Look at this year’s NCAA champs, Vermont, who I had the pleasure to see in person when they gutted out a road win against Pitt here in Pittsburgh. The Catamounts won a sweet sixteen match, a quarter final, a semi and the final against higher-seeded teams. And in two of the four matches – the quarter against Pitt and the semi against our own Denver Pioneers – they played for draws and hoped for the best. They moneyball-ed their way to a title.3

…

I said it was nearly impossible for the moneyball Rapids to win MLS Cup. That’s not meant to be a condemnation. Having followed this team for more than a decade, I' know who they are.

Who they are is a mid-table, low cost team. Yes, we all from time to time get fanatically frustrated that our ownership group KSE don’t spend more on the team. They have a lot of money. They choose to spend that money on the LA throwball Rams and Arsenal Football Club, and to a lesser degree the Colorado Avalanche, but not on the Colorado Rapids or the Denver Nuggets.4 We are not Stan’s favorite toy.

I’m ok with it. The Rapids are not the Yankees or the Galaxy. They are not going to bring in eight and nine figure superstars and blow through the league. They have a plan; the plan guarantees that using affordable methods, and if everything *goes* to plan, Colorado will be in the playoffs each year.

What happens after that is fucking luck.

This is the simplest measure. ASA also has xPts, an Expected Points measure that is created using shots taken and shots faced, run through a simulation, 1,000 times. Both measure still indicate the same idea: if you score more goals than you concede, or take shots that lead to goals and limit the number of quality of shots of the opponent, you will make the playoffs.

One could argue, and many have, that there should be a reward for so-called ‘clutch hitting’; and indeed there is evidence that there are players who hit better in pressure situations than others, meaning RBI is not totally useless. However, on the whole, it just isn’t as important a statistic as others that Bill James and Billy Bean figured out were being underused and undervalued in baseball; namely, On Base Percentage (OBP).

I mean, sorta. They cinderella-ed their way to a title, really. The team construction part didn’t take place with money of course. Vermont’s team was long on foreign players, which is a growing trend in college soccer. Chris Cillizza, a noted political commentator with little to no background in soccer professionally, wrote about it as ‘a crisis’, which would be accurate if college sports wasn’t already in a massively chaotic mess over pay-for-play/athlete exploitation and the excessive use of the transfer portal. Additionally, college soccer has always been for players that didn’t make it to the pros straight away from a pro academy like NYRB or Philly Union, so who cares if it includes players from Spain and Germany? This is a whole ‘nother topic for another time, though.

Is this because KSE sees greater profit potential in those other teams? Is there some kind of algorithm that tells Stan and Josh Kroenke how to maximize revenue but limit expenditures? Does Stan just like throwball more? This is perhaps one of the greatest mysteries.