Backpass: Working Media

There are myriad ways to watch a soccer game. Watching as a photographer is certainly a unique way to be a part of it.

How a given individual engages in the act of watching a sport is as varied as there are individuals, and I find it fascinating. Think of the many soccer matches you have been to, and then think about how different the experience was in each iteration.

Perhaps you have taken someone on a date, and spent the entire match saying stuff like ‘Oh he’s such a great player! I met him once and he signed a soccer ball,’ and then immediately regretted saying it because you now fear you sound like a sycophantic fanboy tool and this pretty girl will be like ‘Bruv I dated three NCAA athletes - two at the same time. You are not on my level.’

Or perhaps you have taken the family to a match and had to do four diaper changes; all inconveniently timed to coincide with all of the key goals of the match.1

Pictured above is my daughter, who is now eight. We once went to a match where she saw the Dippin’ Dots cart. She wanted the Dippin’ Dots. I waited for 30 minutes in line for Dippin’ Dots. I came back, having missed a lot of soccer, and gave her said Dippin’ Dots. She took a small bite, looked at me, and said ‘I don’t like this.’

There’s watching as a noob fan. A whistle blows and everything stops and possession changes and you have to either pretend like you know what just happened, or humble yourself enough to lean over to the guy next to you and say ‘Excuse me. What just happened?’ And that guy will hopefully be exceedingly polite to you as he explains the offside rule.2

There’s watching with a friend you haven’t seen in a long time. The game is pre-text for him finally explaining what a mess his life was before, during, and after the divorce. Suddenly that man chasing that ball, which last week seemed like life and death, doesn’t seem so important now.3

There’s watching experientially - in the Eduardo Galeano sense. Your mind’s-eye zooms in for the clever half-turn; the shoulder shimmy; the cowardly simulated dive just inside the box. There’s watching emotionally, which is similar and overlapping with watching experientially. You are there to exult in the goals. To lament the conceded penalties. To howl with indignation at the referee. It is passion and anger and mucho mucho joy and occasional disappointment4 and utter frustration.5

And there’s watching like a nerd. You try and memorize the lineup when it comes out an hour before the match, and the opposing lineup. You ponder how a 4-4-2 will look against a 4-2-3-1 formation. You wonder whether the spacing is good enough; whether the high-line pressure is effectively smothering the attack; whether the goalkeeper ought to play it deep under the withering press rather than persist in trying to play it out of the back, etcetera. I do this a lot, obviously.

And then, of course, there’s how working media cover a game. To wit (click here to open in another tab):

That guy watches a sport … differently than the rest of us. It’s almost a sport in itself to keep the athlete perfectly in the frame, every single bounce.

Similarly, there are a lot of people working at a soccer match to either provide a service to the fans - the nacho sellers, the security guards, the ticket takers; or cover the game for the folks at home - the camera folks and conical microphone operators and the many, many, unsung heroes like the producers and electrical and digital graphics and the IT team. Their game experience is vastly different than the supporters experience … for being present for the same 90 minutes of football.

As a writer, I often watch the game as an experience, or as a nerd, or as both. When I’m writing a gamer - a game-day recap article - (something, thankfully, I don’t often have to do) I’m paying close attention to every play, especially a scoring opportunity, knowing that I likely will need to describe it in detail for the readers. The whole game is about recording and describing while watching. I hate - HATE - when I’m writing about the goal that happened in the 74th minute, head down, listening in case it seems like something might be about to happen, and I miss the goal in the 76th minute. I feel like a failure. I was too busy writing to be watching. But we can’t do everything, can we?

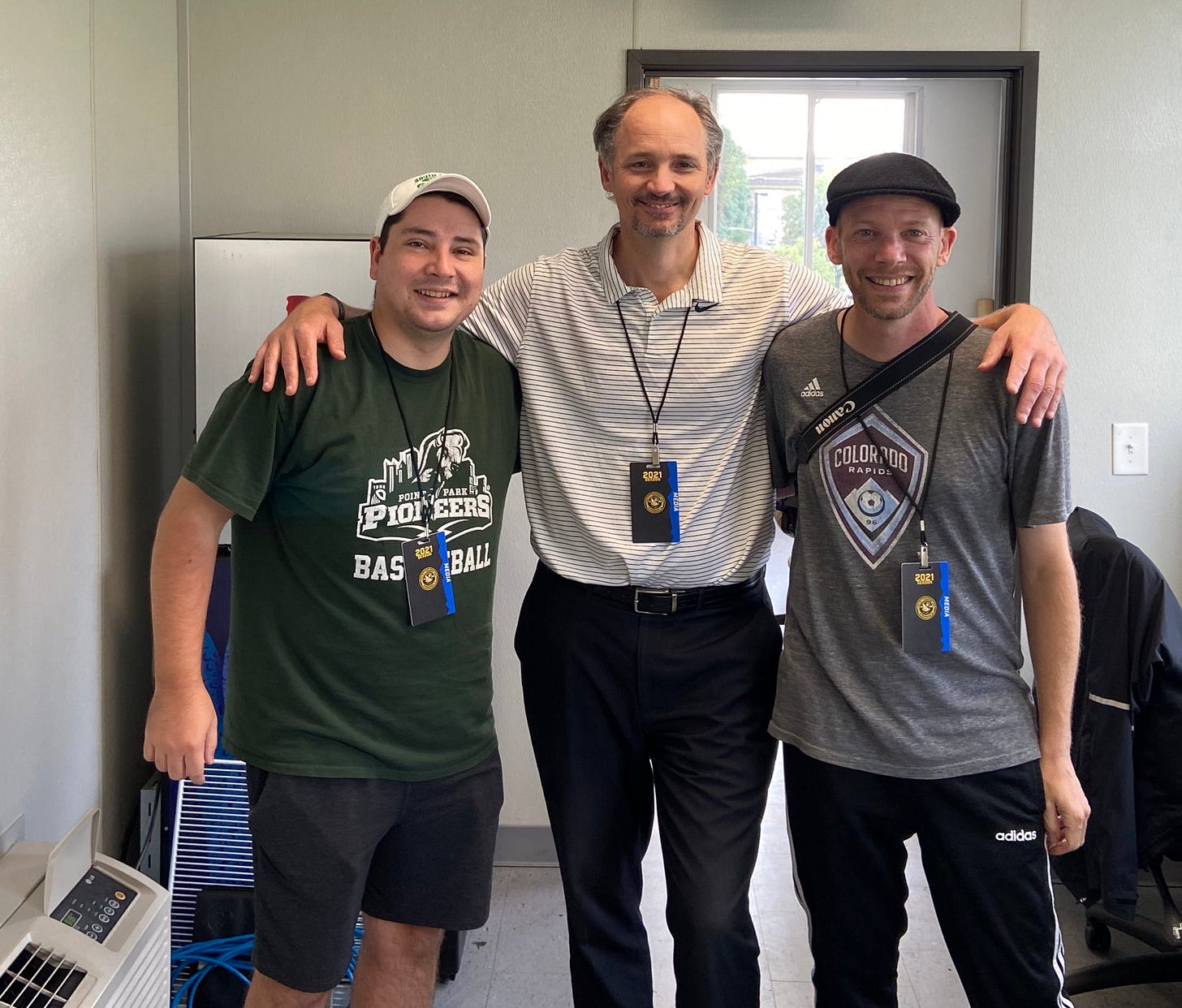

Since deputizing myself as a spare photographer for both Holding the High Line and Pittsburgh Soccer Now in order to vary my skills and my ability to be valuable, I am now watching the game in an all-new way. I am constantly thinking this: ‘where will a great photograph take place, and what do I need to do to get it?’

It isn’t as easy as it sounds.

A photographer has to consider if they want to shoot the home or away team mostly; where the sun is; where the electric signboards are; what the background of a shot might be. If they want midfield action, they need to attach a telephoto. If it’s close-up, they’ll need switch to the standard lens. They might need to vary shutter speed or ISO settings. When a player has the ball, it’s already too late to photograph them - the good photo is as they are about to pass, or right as they receive, or right as they shoot. And a photographer has to anticipate that that is going to happen by thinking actively - ‘where is the ball going next? And then what will happen?’ If I had a good camera, I suppose I could think less and just press a button and rattle off 8 shots in a second. My camera is a ten-year old, used, low-end Canon EOS Rebel. I can take two shots in a second, if I have my s&*# together.

But ‘have my s&*# together’ also means I’m holding the camera steady after a swift movement. The camera must be straight and level to the ground. I need to get the player centered to get autofocus to work right. I need to fill the frame with the action. And take the picture at the right moment. I need to see the player’s face. Another player needs to not be in the way. Additional players need to be either in the frame or out of the frame to the right amount, or it’s not a decent and usable shot.

I am, of course, blessed to live in the era of digital cameras. In the olden days of film and developing in a dark room, I can’t fathom doing what I do now. The other night I shot a Riverhounds game. I took around 175 pictures. After some minor editing, cropping, and light adjustment, I had 27 decent photos. And I only shot the first half.6 I cannot imagine taking 300 pictures - or 6 to 12 rolls of film in the old days costing maybe $50 - in order to get four really good pictures.

As a wordsmith, I might be tempted to wax poetic about any of the pics above, or even talk about ‘the one that got away’. I had this great pic below of the Riverhounds first goal, but you can see that the other players in the shot kinda wrecked it.

I will just briefly tell you about the third pic from the tweet above - the one of Riverhounds defender Jalen Robinson and Miami FC’s Baggio Kcira jostling for the ball. I had a short lens on for close-in shots, and saw Miami’s midfielder square it up for a cross to the left, so I adjusted myself to focus on Kcira. He received the ball and pushed it out in front of himself, and the two players immediately start shoving and running for it.

In my head, I repeated to myself: ‘Focus. Get it all in frame. Wait to click. Do not be afraid. Yes, they might hit you. But this is going to be a great shot.’

*Click*

It was a very good shot - although slight out of focus! (arrrrgggghh)

Robinson bodied Kcira off the ball. The ball rolled up and hit me on the knee. The players, thankfully, did not truck me over.

A second later I got these two also, which aren’t really useful, but hey, I tried.

At the half, working media are … working. Our editor John needed photos for the recap, and ideally one by games-end, so rather than actually watch the rest of the match, I was uploading, sifting and editing; uploading, sifting, and editing. The Hounds lost 3-2. I only saw the first goal, and from the wrong end, and as you saw, the photo didn’t come out well. So a good match, but a humbling one, and a learning experience. I got lots of stuff for file photos of Miami FC, so I did my duty for the company on this night.

Strangely, when you work the game, your focus narrows - no pun intended. You need to burn a moment into your brain, or find the perfect photo, or uncover the right statistic that will explain the balance of the match properly. You think about the game very differently. Guiltily I will admit that when I am writing the recap, I am often rooting *against* action in the final five minutes. A last-minute winner or equalizer can completely destroy the opening paragraph - or even the bulk of the narrative - of the match. Every recap writer has been baptized at some point in the fires of having written six paragraphs that begin ‘It was a defensive struggle here in Commerce City…’, only to have the two teams score four goals in the final ten minutes, at which point you quietly mumble “F********” and delete everything you wrote over the past hour.

As a photographer, you are playing your own game, and then doing your own recap. ‘Did I get the right shots? Why or why not? How could I improve for next game?’ And as you edit, you suddenly don’t even care what happens in the match. You just want to provide the perfect photo to lead the article.7 And then, when you do, it all feels worthwhile.

I love to work a game - in any way that produces something valuable for readers. But I certainly am reminded, from time to time, that as much as I love working it, being there without obligation just to watch and enjoy is really the purest soul of the watching experience. As much as sometimes folks rightfully envy the reporters and photographers that get up-close access to the match, sometimes us worker bees are envying you in the stands, beer in hand, experiencing the joy of football, weightless of its obligations.

I took the fam to a Rockies game once and, while carrying my 8 month old daughter up the stairs, my shorts caught on an armrest and slipped to my knees. I calmly handed my daughter to a complete stranger in the 15th row, adjusted my pants, snatched her back, muttered ‘thanks’ and continued on my way. Sleep deprivation makes you do strange things.

I personally have explained the offside rule at least six times at a Rapids match. Actually, I really enjoy it. We should all try to be emissaries of the game and explain stuff without a hint of arrogance. We were all noobs once.

Many moons ago I went to the Rapids-Sounders 2016 playoff game in Seattle. The game was clearly important, but my good friend revealing the messy details of his marital turmoil was clearly far more important in the grand scheme.

In 2015, 2017, and 2018 - Frequent disappointment. Constant, even.

If you have Comcast or Dish, and you can’t get a VPN to work, then you understand ‘utter frustration,’ because you can’t watch the Rapids games at all. Or the Nuggets or Avs.

When it gets a bit darker, in the second half, my camera really struggles with action blur and light balancing, and the odds of a good photo go from 10% to 1%.

Sometimes your best five photos on the night - are wrong for the writer’s story. If you have the world’s greatest pic of goalkeeper William Yarbrough saving a ball - like Pulitzer Prize composition, kids - and the Rapids lose 5 to 0, that pic ain’t seeing the light of day. It doesn’t fit the narrative. A few weeks ago I needed a great pic of Sam Vines. And we just… didn’t have one. Sigh.